“Curating Change: The Potential of Social Work in Transforming Museums”

By Alexandra Rose (UNC Social Work ’24)

Summer 2023 AFE Blog Post Series

As a social worker primarily interested in galleries and museums, I’m used to explaining my professional trajectory to people when they appear confused. I have been building the connection – social work and museology – for some time, and by now, I have solid answers to the many questions that arise. Although the overlap works in theory, admittedly, I have limited experience of putting it into practice. In many ways, my Applied Field Experience (AFE) is the test case of stepping into a heritage institution and embodying the intersection of two different but aligned professions. “I’m here to bring a social work perspective to your museum collection” said no Rotary Peace Fellow ever, at least until now.

As a social worker primarily interested in galleries and museums, I’m used to explaining my professional trajectory to people when they appear confused. I have been building the connection – social work and museology – for some time, and by now, I have solid answers to the many questions that arise. Although the overlap works in theory, admittedly, I have limited experience of putting it into practice. In many ways, my Applied Field Experience (AFE) is the test case of stepping into a heritage institution and embodying the intersection of two different but aligned professions. “I’m here to bring a social work perspective to your museum collection” said no Rotary Peace Fellow ever, at least until now.

I’m now three weeks into my work with National Museums Liverpool, working with the teams of the Global Cultures Gallery and the International Slavery Museum. Even in these early stages, I can definitively say that the openings for social work in the museology field are far bigger and richer than I could have imagined. As a refresher – social work combines a skill set and mindset, valuing human rights, equality, and social justice. It prioritizes the human experience, acknowledging the interconnectedness of individuals and systems. By starting at the individual level, social work intervenes in complex power dynamics, addressing both institutions and individuals to create meaningful change. So, what does all that have to do with museums exactly?

This blog post is an account of my first week of AFE. Some of what I know best is questions[1] so at the end of each section, I have included a question which comes from my own observation of the work and what is at the forefront of my colleague’s minds as they navigate this complex cultural terrain.

Monday: The Global Cultures Gallery (GCG) team takes me on a tour of the exhibits. The collection comprises approximately 40,000 items, only 1% of which are on display with the rest in storage (more about this on Thursday). During the walkthrough, we discuss how the collection is an “ethnographic collection”, which means that the materials on display are objects collected from “other” or “exotic”[2] cultures outside of Europe. Communities who were the original custodians and owners of the objects are closely examining such collections, rightfully expressing feelings of being othered, stereotyped, and misrepresented.

Along with broader ideological shifts in society in general, most people now acknowledge the inherently problematic way that culturally significant items, most of which were stolen or looted, are displayed in glass cabinets within European museums, where an entire cultural and spiritual history can be subsumed under a broad label, like “Oceania” for instance. The team walks me through the gallery as we discuss this. There is a lot of transparency and knowledge of these problems, and as a result, most of the team’s work is now about decolonising the collections and acknowledging past injustices. They talk to me about their responsibility as curators to now “care for” this collection of objects and their ambitions to make the exhibits more representative.

Question: How can we design future exhibitions with originating communities in ways that more truthfully tell the history of how and why these collections came together?

Tuesday: Today, I handled several items classified as Benin Bronzes. We are preparing the items for transport to a different museum. The term ‘Benin Bronzes’ refers to several thousand plaques and sculptures originating from the Kingdom of Benin (the Kingdom is within what is now southern Nigeria), many of which are scattered across European museums. The history of how they ended up in Europe in the first place is violent, upsetting, and painful, and many Benin Bronzes are subject to international repatriation claims. As I hold the bronzes and look carefully at them, it’s overwhelming to consider the life of this object, its significance, its cultural value, and the grief associated with its absence. I try to savour the privilege of this present minute which exists as a bridge between the past and the future. We carefully wrap the objects and prepare them for travel.

Question: Given that the very concept of a museum is a Eurocentric idea, what stories do we need to centre as we redefine what museums can do for our society right now?

Wednesday: We discuss policies the museum is developing regarding repatriating culturally significant objects and human remains. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples has set forth clear guidance on the repatriation of human remains and funerary objects being returned to individual tribes. Having these policies in place and accessible to the public affirms that the GCG wants to respond to each claim with an action-oriented disposition and a mindset that promotes the healing of the communities that make claims.

In the evening, I attend a meeting with UK museums and Indigenous communities from the Northwest Coast of Canada. Originating communities do not always know where their belongings are overseas or which museums are holding onto them, so in this meeting, the different museums share summaries, photos, and information about the Pacific Northwest Coast objects they are holding with the intention of renewing relations and opening channels of communication.

Question: How can repatriation processes be designed in ways that intentionally intersect with reconciliation and social healing?

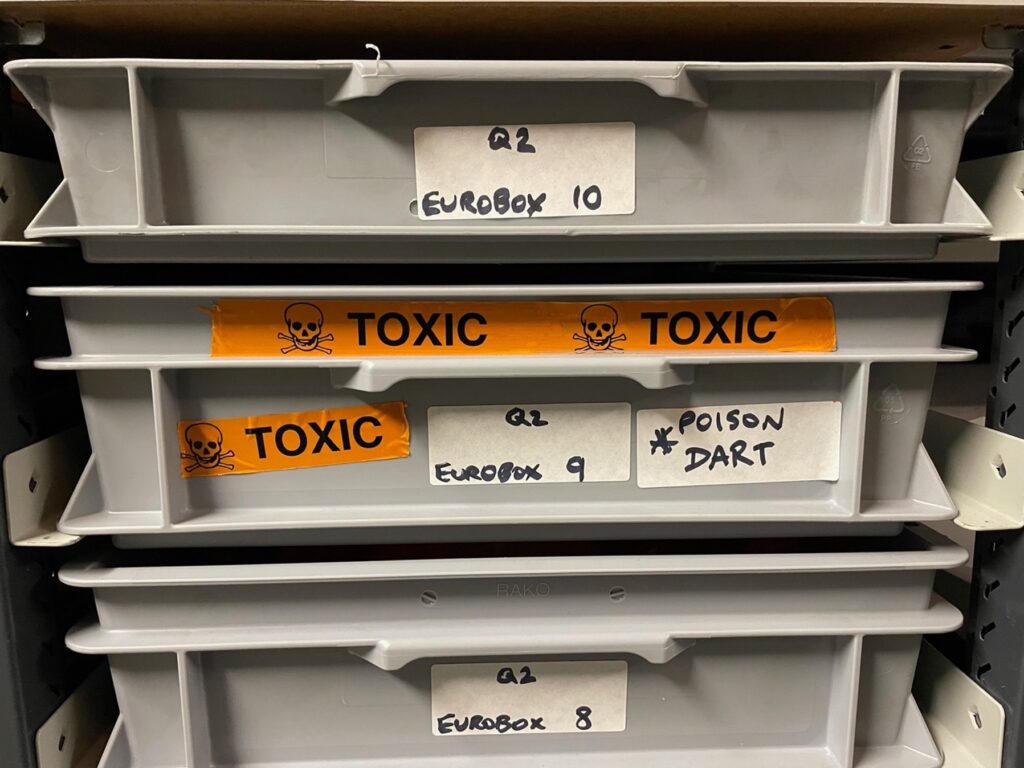

Thursday: I’m spending the day inside a huge complex of about 12 adjoining warehouses which store the objects of National Museums Liverpool when they aren’t on display. I’m surrounded by hundreds of rows and racks of objects. There are 3,000-year-old Egyptian inscription fragments on my left side. On my right side are decorative spoons made from coconut shells from the Pacific Islands. The next row over a box is labelled TOXIC – POISON DART, and opposite that, Canadian Aboriginal quillwork fans. It is quite overwhelming to consider the incredible cultural objects surrounding me. Each artefact is labelled and organised and kept in temperature and light-controlled conditions. Today, the team are researching and organising objects ahead of a visit by a Filipino research group trying to locate objects of cultural significance for their community.

Question: How do curators adapt their care practices for objects as museums become alive to the ethical and moral dilemmas of maintaining ethnographic collections?

Friday: I’m spending the day with the curatorial team from the International Slavery Museum. As they walk me through the current exhibitions, we discuss how trauma-informed practice could play a role in the upcoming redevelopment of the museum. Putting on a clinical social work hat, I can spot areas where exhibits can be more trauma-sensitive while still encouraging visitors to acknowledge the discomfort that comes with learning about challenging histories. We discuss their hopes for the space to be both thought-provoking and empowering, and I share the ways in which trauma-responsive design offers some useful parameters.

What is best practice for museums when exhibiting objects that memorialise and tell histories of violence and trauma? How do we care for staff as they undertake this important work?

I hope that asking these questions will be my life’s work. They are important questions to ask. But I keep remembering that they cannot be asked without engaging in self-reflection and asking hard questions about my own positionality and privilege. My relationship with power is strengthened through the opportunities provided by the Rotary Peace Fellowship. The inner work required to ethically and intentionally step into this power is profound and never-ending.

[1] Thanks to adrienne maree brown’s writings for this revelation.

[2] Here I am using quotation marks as a signpost for the fact that these labels are highly problematic.