“L’Esprit de Genève – A Lifelong Quest for a Zambian Rotary Peace Fellow”

By Gibson Zulu (UNC Global Studies ’24)

Summer 2023 AFE Blog Post Series

‘What does a Rotary Peace Fellow do?’ What professional work or business are you doing in Geneva?’ These are the questions I got from a senior Rotarian who belongs to the Rotary Club of Geneva International when I went for the second meeting. He had a point! Shouldn’t I have traveled to Malakal or Juba in South Sudan or Goma in Eastern DRC instead of Geneva? After all, there is no conflict in Geneva that would warrant the presence of a Peace Fellow, but South Sudan and DRC do. To answer his question, I will let you in on what I do for a living first.

‘What does a Rotary Peace Fellow do?’ What professional work or business are you doing in Geneva?’ These are the questions I got from a senior Rotarian who belongs to the Rotary Club of Geneva International when I went for the second meeting. He had a point! Shouldn’t I have traveled to Malakal or Juba in South Sudan or Goma in Eastern DRC instead of Geneva? After all, there is no conflict in Geneva that would warrant the presence of a Peace Fellow, but South Sudan and DRC do. To answer his question, I will let you in on what I do for a living first.

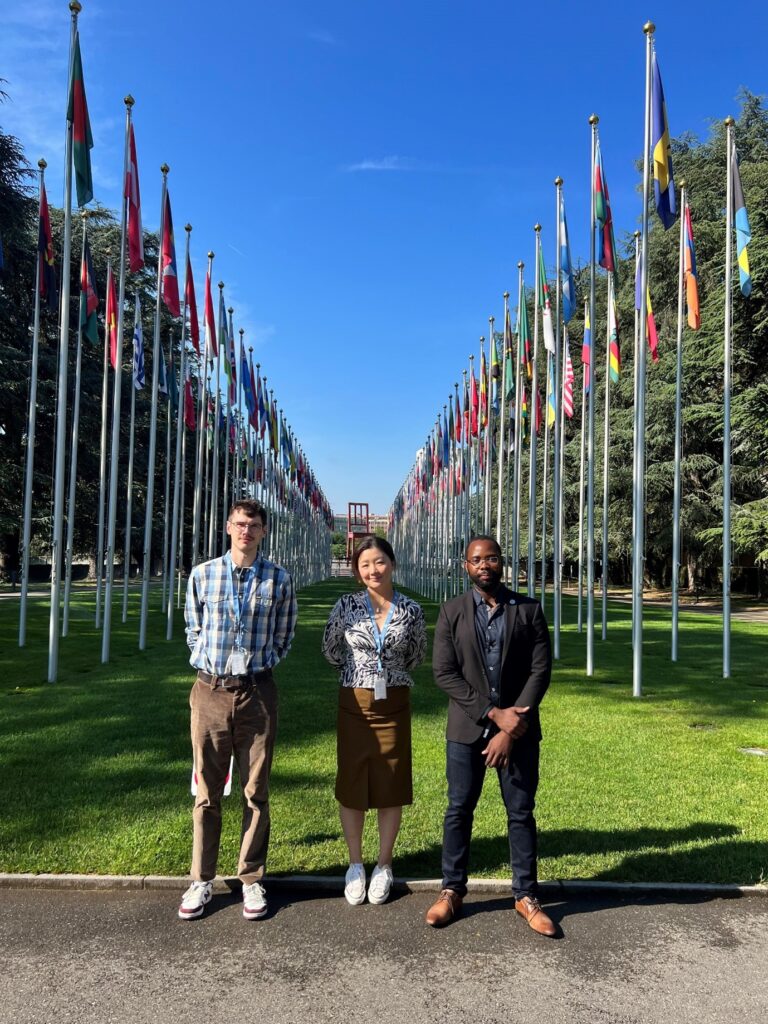

I arrived in Geneva, the capital of peace, human rights, and humanitarian work on May 11th, 2023 to start my work with OCHA-NARAS (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs – the Needs and Response Analysis Section) as part of my Applied Field Experience as a Rotary Peace Fellow. I have never worked in an “A” duty station before as my entire career in the humanitarian sector was forged in hardship duty stations in the deep field, as per the humanitarian parlance. Deep field denotes remote towns or cities in developing countries characterized by inadequate infrastructure, poor amenities, and facilities in far-flung places where some people would wonder what it is that you are running away from back home.

So, what does a Peace Fellow do and what is the purpose of my visit to Geneva? I gave him a metaphor of a smoke jumper. A Peace Fellow is akin to a smoke jumper, skydiving into infernos to put them out and protect the environment, property, flora, and fauna. Smoke jumpers work in tandem with local partners and government officials to quench wildfires. No matter how advanced technology for detecting and fighting fires gets, the fires show no signs of abating, and smoke jumpers don’t stop responding either. Peace Fellows operate similarly in their endeavors to extinguish conflict and make peace. Unlike wildfires that smoke jumpers are accustomed to fighting, Peace Fellows transform intra-state conflict to make peace between belligerents and local communities. The purpose of training Peace Fellows is to create a cadre of young leaders through rigorous academic training, professional networking, and the applied field experience which brings them back into the professional orbit. These leaders are supposed to go into fragile and conflict-riven countries to be embedded with local communities and design joint solutions to conflict, with the locals leading the process.

Before my Geneva professional development stint, let me take you back to 2011 where it all began. I started my journey with the United Nations in December 2011 after my undergraduate studies at the University of Zambia. I interned with the Resettlement Department of the UN Refugee Agency in Lusaka where I learned how to process refugees for resettlement to the US, Canada, and Australia. Fast forward to July 2017, I flew to Liberia as an international UN Volunteer, the first Zambian to have become one. I was assigned as a Durable Solutions expert because Zambia was the first country to have implemented local integration in Africa. I was to lead the implementation of the local integration programme in Harper, Maryland County where I oversaw the transition of the local integration programme from UNHCR led to the Liberian County government. My last flight out of Liberia was bittersweet in August 2021, and I made my way to Ethiopia to lead the coordination of refugee protection and durable solutions for 12,000 refugees from Sudan, South Sudan, and Eastern DRC. Living in a refugee camp is something I had never done in my life before. I worked in camps but never lived in one. The half a year I spent in Ethiopia in the Sherkole Refugee Camp working with subsequent generations of refugees who were born in exile as refugees prompted me to seek the tools to resolve conflict.

Protracted conflict is the major causative factor of forced displacement. The UN Refugee Agency was created by Resolution 319 A (IV) of December 3, 1949, during which more than 40 million refugees had been displaced within Europe after the Great War[1] . Right now, the figures are at more than 103 million forcibly displaced people globally[2]. Durable solutions are elusive given the protracted nature of war, and less than 1% of refugees can be resettled in developed countries. My time dedicated to implementing durable solutions in 6 refugee camps spread across Southern, Western and the Horn of Africa with Angolan, Somali, Rwandan, Burundian, Eastern DRC, Ivorian, Sudanese, and South Sudanese refugees inspired a strong interest in addressing the root causes of war. Humanitarian aid operates in a palliative mode and merely puts a band-aid on a deeper wound. All these countries have one thing in common – protracted conflict. That was my lightbulb moment. To reduce the risk of bequeathing refugee status to new generations, I had to be a messenger for peace who would travel to conflict-riven countries and work with locals to seek solutions to conflict. Doing that warranted obtaining the right tools and a conflict resolution toolbox. Thus, I applied for a Rotary Peace Fellowship to the Duke-UNC Rotary Peace Center in the United States of America.

Studying in the US exposed me to distinct elements of international economics, research, development, conflict resolution and global migration to which I was oblivious. I realized that there was so much I never knew, but I eventually got the right tools in my toolbox to dive into a conflict zone and get to work with locals. All peacebuilding is local. Of course, I am not naïve. Conflict is as old as humanity itself, and although we may not eradicate all the wars globally, silencing the guns in one conflict is reason enough to never give up. I refuse to believe that certain countries are doomed to a vicious cycle of incessant conflict and fragility as has been commonplace in the DRC and South Sudan.

Now, fast forward to Geneva where I am embedded with the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Needs and Response Analysis Sections (NARAS), the thinking and planning branch of the APMB (Assessment, Planning, and Monitoring Branch). My initial dream was to work in South Sudan or DRC for ‘the real rewards of working for the United Nations are in the field where people are suffering and need you’ (these were the words of Sergio De Mello, the irreplaceable consummate UN diplomat whose loss will forever be felt by the UN). I could not get a placement in South Sudan or the DRC, hence I ended up in Geneva.

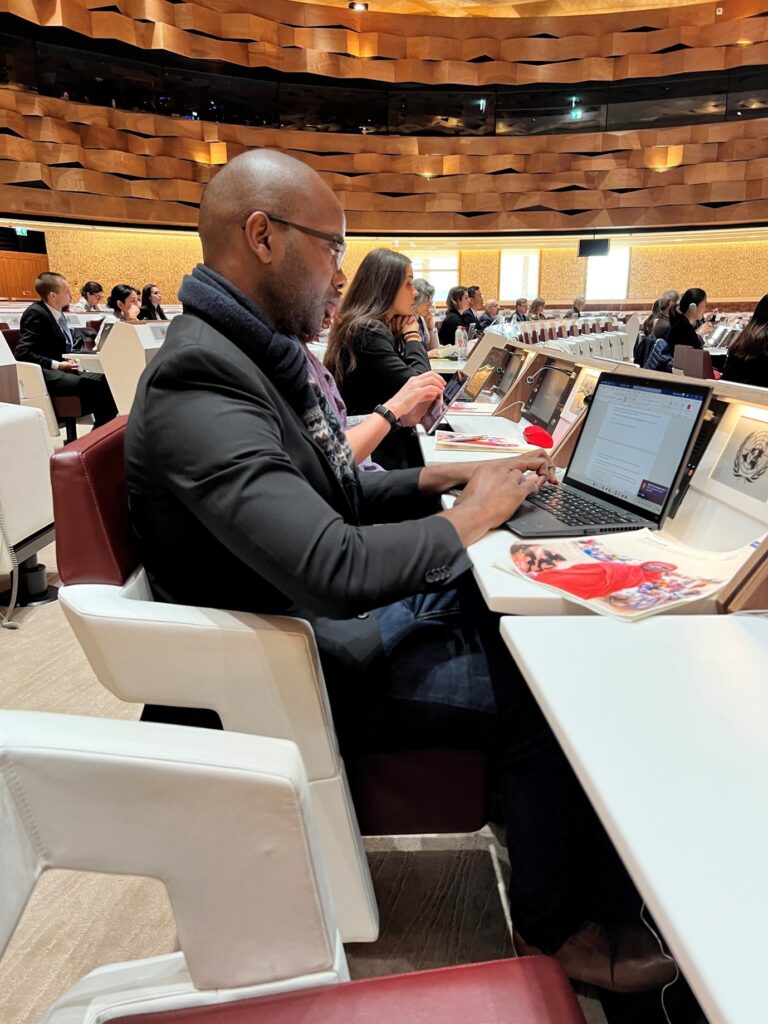

My job involves overseeing support to OCHA colleagues in Sudan and CAR by conducting secondary data research and analysis and producing succinct reports and actionable data on conflict and flagrant violations of International Humanitarian Law. These are needed to aid humanitarian access in a conflict zone using the aid of the DEEP platform (DEEP.io), an artificial intelligence open-source platform for humanitarian workers. Humanitarian workers, donors, and UN agencies get inundated with copious amounts of data that need to be condensed to make them actionable and valuable. My work saves aid workers time and money by providing custom-made data meant to guide decision-making and operational responses by cluster leaders. I also recruit online UNVs who operationalize the projects.

I flew into Geneva on May 11th and witnessed the launch of the revised Humanitarian Response Plan for Sudan and the Regional Refugee Response Plan for countries responding to the Sudanese crisis. Being in a room full of member states including the P5, mature and emerging economies who made monetary pledges and in-kind aid in the form of medical drugs, vaccines, food, water, and clothing for the Sudanese crisis gave me a sneak peek into how humanitarian assessments and resource mobilization are done at HQ. These upstream activities are indispensable to the humanitarian programming cycle as resources are a prerequisite for conducting humanitarian aid. Being in Geneva has made me realize that humanitarian work is akin to a production line where everybody plays a role in a collective endeavour to attain the same objectives. Fieldwork involves downstream activities, but HQ is where the support that is delivered in the field emanates. Some of the greatest challenges I encountered working in the humanitarian sector included elusive durable solutions due to protracted conflict, inadequate funding and limited livelihoods and education opportunities for women and girls. Resource mobilization with donors and or the private sector is one way of making a solid difference, and I love the aspect of my job that involves providing remote support to field colleagues in the Central Africa Republic and Sudan and shuttling between meetings with member states who are responsible for purveying and bankrolling global peace.

You will never read about the invaluable work that United Nations member countries do to save lives around the globe wherever there is a crisis globally in mainstream media. You may think that global solidarity is biased towards some countries, or that the world is headed for Armageddon, because you are not privy to the work of the custodians of peace and human rights based in Geneva.

So why am I here? I believe my time in Geneva will expose me to the architecture of upstream humanitarian activities at HQ that I will exchange with local staff and civil society when the time will come to get on a plane and dive behind the front lines to build peace, just as smoke jumpers dive into infernos.

My return flight to the US is scheduled for mid-August, and leaving Geneva will be bittersweet. There is something about the soul, culture, and spirit of Geneva and Switzerland that is unrivaled. Here is where I have found my true calling. L’Esprit de Genève is one unique conflict resolution tool I will be carrying back to the States and later to South Sudan and DRC after my graduation. Go Heels and Imagine Rotary!

[1] https://www.unhcr.org/media/state-worlds-refugees-2000-fifty-years-humanitarian-action-chapter-1-early-years.

[2] https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/